Working with Natural Watercolor Paints

- Alison Webb

- Jan 30

- 2 min read

Natural watercolor paints are a delightful way to capture the beauty of a flower that grew in your garden, to repurpose a noxious weed, or to admire the colors each season brings. Whether you purchased paint from me or made your own at a workshop, this guide has useful information on working with your paints.

Storage

Allow your paints to dry thoroughly before storing them in a closed container. The binder used in these paints contains clove oil, which helps prevent microbial growth. The clove oil and proper storage will keep these pigments indefinitely. Natural pigments can fade in sunlight, so it is recommended that you store them in the dark.

Painting

These handmade, natural paints can be used in the same manner as commercially available watercolor paints. Once applied to paper, water can dilute and rework the color. Allowing paint to dry between applications can develop layers.

You will want to begin by rewetting the paint. A natural humectant (honey) is added to the binder to speed up this process. Allow the water to soak into the dried paint before you begin painting.

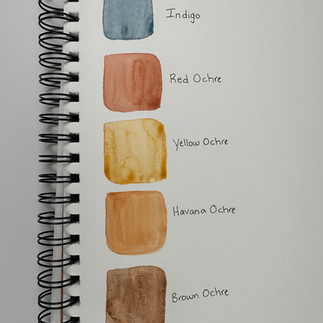

Granulation

Some paints naturally granulate, meaning the pigments on the paper's surface will separate or clump together. Many Earth pigments and Indigo paints will naturally granulate, as will anything mixed with them.

Secondary Colors

Generally, natural pigments will create the expected secondary colors when combined. In the first image is a color wheel made with Tansy (yellow), Madder (red), Indigo (blue), and their combinations.

Dark pigments like charcoal (Midnight Shimmer) and Black Walnut can be used to tint other colors. Shown in the second image is Tansy mixed with increasing concentrations of Black Walnut (left) and charcoal (right).

Mica can add shimmer when combined with any color (image 3).

Lightfastness

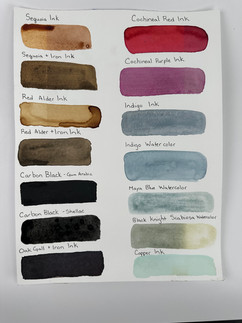

Lightfastness refers to how well a pigment can tolerate UV exposure before fading. Natural pigments vary significantly in their lightfastness. Generally, earth & mineral pigments, indigo, tannin + iron combinations (oak gall ink), charcoal, and high tannin pigments (black walnut) have excellent lightfastness. Botanical pigments, especially yellows, have poor lightfastness. Anthocyanin pigments found in berries, purple/red fruits, and vegetables have extremely poor lightfastness.

You can test a pigment's lightfastness by exposing it to sunlight and observing how much it fades. Below is a lightfastness test I ran by covering a portion of the paint or ink with black paper and placing it in a sunny window for six months. The botanical and mushroom-derived yellow pigments exhibited significant fading, as did the anthocyanin-based Black Hollyhock & Black Knight Scabiosa, which nearly disappeared.

I wouldn't let the lightfastness of a pigment prevent you from using it. Working in a sketchbook, which is often closed and away from sunlight, is a great way to use pigments with poor lightfastness. I think this is one of the strengths of using natural pigments as paints & inks over dyeing textiles, which are more challenging to use without exposure to sunlight.